The roots of what is now the small city of LaFollette stretch back well before the Revolutionary War. It once had the postal address of English, then London, and then Big Creek Gap.

The roots of what is now the small city of LaFollette stretch back well before the Revolutionary War. It once had the postal address of English, then London, and then Big Creek Gap.

It became LaFollette in 1897, named for Harvey LaFollette, who came here from Wisconsin with his brother to establish the LaFollette Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company in 1892. They bought almost 40, 000 acres, renamed the village of Big Creek Gap after their family, and began vigorous exploitation of the areas coal, iron ore, limestone, and timber. To do that, they also built a stretch of railway, the Tennessee Northern, and sold it to Southern Railway Company.

The LaFollette’s hired John Fox Jr., famed Appalachian author, and friend of presidents, to draw the plans for the city of LaFollette. He was farsighted, laying out wide streets, unusual for mountain towns, plus parks and lots for churches.

LaFollette then established a bank and began planning to move the courthouse from Jacksboro, against much resistance and political chicanery. He finally won the battle, and in February 1904, courthouse offices moved into a building in LaFollette. The following May 10, fire swept down both sides of North Tennessee Avenue and along the north side of Central Avenue. Thirty-five businesses were lost. The county seat returned to Jacksboro and has remained there since.

Unfortunately, LaFollettes business ventures faltered. The quality of the iron ore in the area was poor. And then after a few years, the businesses failed and the LaFollettes left the area. LaFollette’s population in 1900 was about 366. By 1920, the population had grown to 3,056 and Harvey LaFollettes various enterprises employed 1,500 of them. In 1928, the employment had declined to about 600, and the businesses were sold.

LaFollette lies in the mouth of the fertile Powell’s Valley, which began at Harrogate to the east — a wide crease in the Appalachians. Cumberland Mountain forms the north edge of the valley all the way to Caryville. Big Creek (or Indian River) runs through the center of town. It is more a creek than a river but, in the 1950s, overran its banks and flooded the center of town. On the southern edge are low lying hills and Powell’s River, which flows into Norris Lake, formed by the Tennessee Valley Authority’s first dam, Norris, closed in 1936.

For many years, the main north-south route through mid-America was up and down US 25-W, through downtown LaFollette, and the traffic brought lots of business for restaurants and gasoline stations. But Interstate 7 5 was being built, and it already had reached Lake City. All the traffic that had come through LaFollette, bumper to bumper along North Tennessee Avenue, with half a dozen restaurants, had suddenly stopped. Most of the restaurants had closed, leaving the street like a ghost town.

As time passed, remaining businesses began to wither as chain stores moved into the area, building on the outskirts of LaFollette.

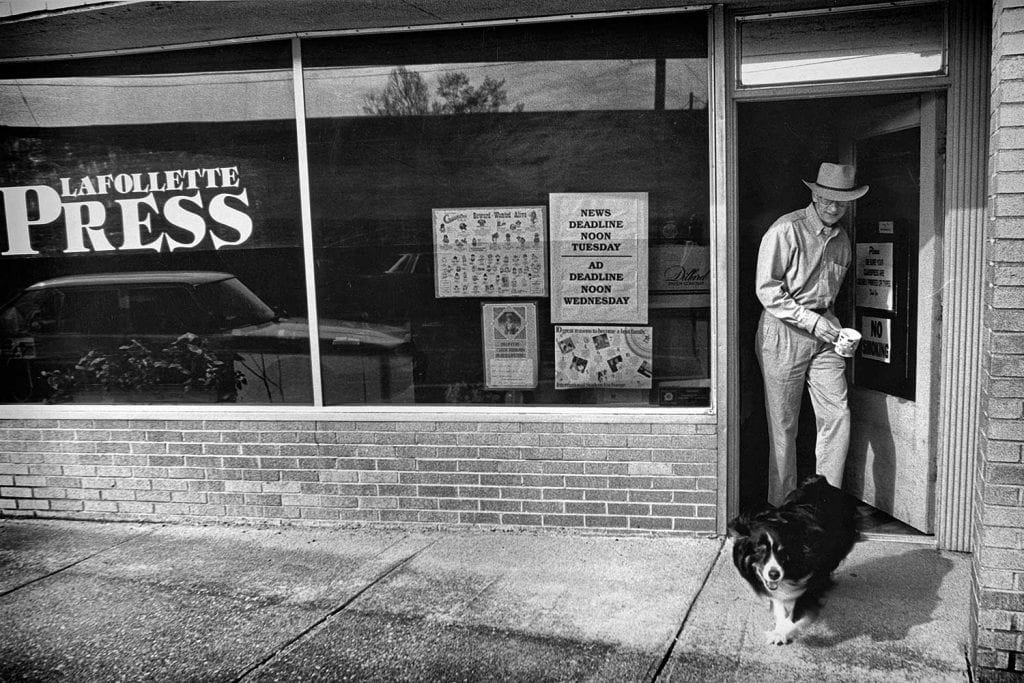

In 1969 I moved to LaFollette after purchasing an interest in the local newspaper, the LaFollette Press. One of the continuing features I’m proudest of is the Eyes on LaFollette section that began in 1993 and continues as a legacy to Press readers. My good friend Rob Heller, photojournalism professor at UT, suggested back in 1993 that he bring his photojournalism class to LaFollette to chronicle life in a small town. I jumped at the idea. And each edition captures new images that help define a small town in Appalachia.

Their greatest contribution is preserving unique images of the fiercely independent people of LaFollette and its surrounding area in their everyday activities.

It’s not about the buildings or the particular businesses. It’s about the people.

That’s the REAL LaFollette.

Larry Smith, Publisher

LaFollette Press 1969-2002